"What we see is that many interventions that are shown to lead to positive results for patients, and are often already a part of national guidelines, are not utilised enough," says Hoogendijk. "What is worse, is that the use of interventions varies greatly depending on which country or region you live in. I can imagine that this is frustrating for patients," he adds.

Physical Activity

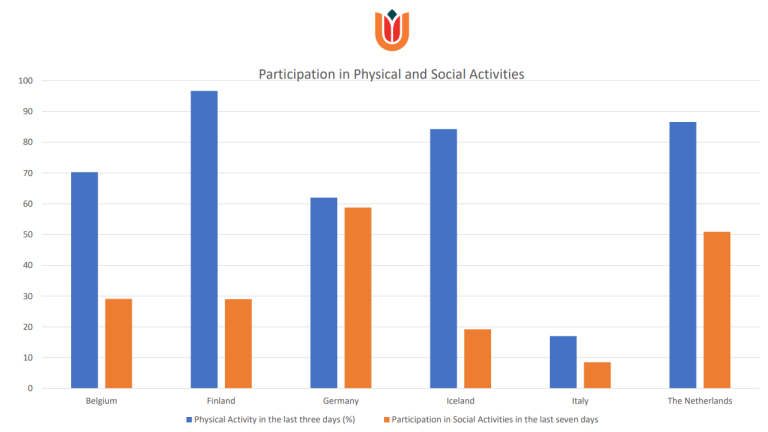

Across all 6 European countries, some interventions were almost uniformly present with exceptions. The most significant exceptions related to physical activity. “We see in the data that when it comes to physical activity the numbers vary greatly. In the Netherlands more than 80% of patients have been outside in the last three days, whereas in Italy is this only 7%,” says the study's lead author, Eline Kooijmans.

Physical activity has been shown to reduce the recurrence of falls as well as improving both social participation and daily functioning, particularly of those with dementia. Daily function is also improved by social contact, a factor that also varied widely across the six countries.

Negative effect on health outcomes

The Amsterdam UMC researchers analysed patient data from almost 3000 homecare patients across Europe finding a "relatively high prevalence” of physical restraints, such as bed rails or mobility-limiting chairs, in Germany and Italy.

"Studies have shown that the use of physical restraints may have a negative effect on emotional wellbeing and a patient's physical functioning, while at the same time the evidence that they prevent falls is lacking. In fact, research has shown that restraints may cause more falls, likely through a lack of physical exercise. This is something that health care systems should really be alert to," says Hoogendijk.

Low-hanging fruit

Research has already shown that the amount of formal care, provided by organisations, is higher in the Netherlands, Belgium and Scandinavia than in Mediterranean countries and in this study this finding is reinforced. In Italy, less than 4% of patients received help to tidy their homes, while this more than three-quarters of patients in Iceland received some sort of help at home.

"What we see, across almost all interventions, is a very fragmented picture that isn't accounted for by other factors such as whether or not patients had informal caregivers in their networks. Nevertheless, these results show that there is really some low-hanging fruit waiting to be plucked in many countries, when it comes to older care recipients. Something that is only going to become more important as the population ages across Europe,” concludes Hoogendijk.

Future care is personalised

The same researchers are involved in a follow up study, I-CARE4OLD, which is coordinated by Hein van Hout, professor at Amsterdam UMC, “We develop a decision support tool that is able to estimate an older person’s prognosis more precisely. This digital tool also advises on the beneficial or harmful impact of specific interventions. We apply machine learning using high quality routine care data of millions of older care recipients across 8 countries. I expect that this tool can decrease the huge unexplainable variations in treatments across similar patients and increase care quality in this way.”