Her research shows that these barriers exist at all stages of life: at the end, in the beginning as well as throughout the various screening programmes that we all are subject to throughout our life.

Beginning of life

"Language barriers often impede access to good quality healthcare. When faced with a language barrier, healthcare providers often “get by” with help from family and friends rather than professionals. This jeopardises good care,” says Suurmond.

Research has demonstrated that midwives were found to omit or simply information about prenatal screening, when faced with a language barrier. Leaving women with insufficient information on which to base their decision over screening.

"Another impediment is the assumptions and stereotypes that care providers may have about a patient. For example, in the same study we found that midwives sometimes skipped some information about prenatal testing when they felt that their client would not accept the test anyway due to religious reasons,” adds Suurmond.

Also, later in the life span, when sick children have to be admitted to the hospital, the research of Suurmond shows different linguistic, cultural and other barriers that hinder good care. For example, Suurmond adds, “in burn care and in paediatric oncology care, healthcare providers struggled with providing good information to parents about their child's condition across language and cultural barriers. As a consequence, parents were not always aware that their child was not doing well, or – the other way around – believed that their child would remain severely handicapped when in fact the doctors felt that the child would recover completely.”

Lowered Participation

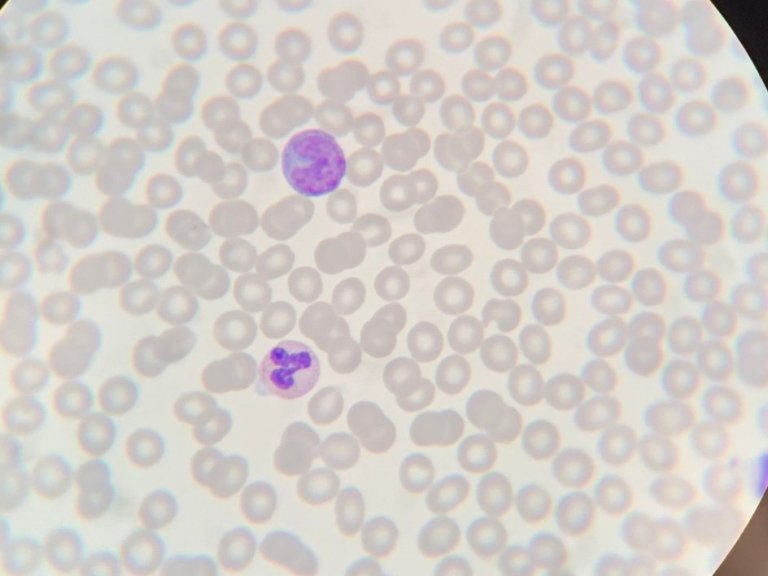

Research has shown that ethnic minority groups are less likely to participate in screening programmes that the majority population, meaning that they are also less likely to be diagnosed early. Colorectal cancer, the third most common global cancer, develops silently, thus a failure to diagnose decreases the survival chances of the patient. Individuals often believed the opposite: that cancer only affected those with symptoms. This was partly caused by a language barrier, something that has further consequences.

In the case of colorectal screening, this means that "due to linguistic and cultural barriers elderly migrants encountered all kinds of difficulties. As the screening for colorectal cancer is a self-test, participants did not understand the instruction to carry the test out, because they could not read the Dutch text. And when their children offered help, they felt too embarrassed to talk about cancer or about faeces with their children," adds Suurmond.

End of Life Care

The difficulties caused by living in a country where you can't communicate in the national language also affect those at the end of their lives. Research from Suurmond and Amsterdam UMC colleagues, has shown those with a non-western migration background are more likely to be admitted to and die in hospital than those with a Dutch background. Patients with a non-western migration background were also less likely to receive morphine and other sedative medication and, perhaps most impactfully, more likely to receive end-of-life care that, in the view of physicians, continued to look for a cure for too long.

Suurmond and colleagues' research recommends interactive meetings organized by migrants for migrants and their families to give information about the Dutch system of palliative care. Understanding of palliative care also means understanding the religious beliefs of patients and – as healthcare provider – look for middle ground together with the patient and family rather than to dismiss religious or cultural needs that patients and their family have at the end of the patients’ life.

Stepping over the Barrier

Previous research from the University of Amsterdam has shown that migrant patients ask fewer questions in comparison with ethnic Dutch patients, and they are less involved in shared decisions with their healthcare provider about their own health and healthcare. This shows that having good intercultural and interlinguistic communication skills is crucial. "All healthcare providers and students should be trained to work with professional interpreters. Professional interpretations services should preferably be free of use," concludes Suurmond.