"Social and cultural factors play a role in our lifestyle behaviours but so do our genes and the environment in which we live and work. Residents of neighbourhoods are not equally exposed to unhealthy factors: one might have more exposure unhealthy food outlets and fewer sport facilities than the other. We call these “obesogenic environments”, an environment that promotes weight gain or prevents weight loss. In a European context, this has never been properly mapped and studied, while we may be able to improve the health of millions of people with it,” says Lakerveld.

Obesity is, after smoking, the leading global preventable cause of death and more than half of European adults are now overweight, including obesity. Obesity increases the risk of a number of chronic diseases, including cardiovascular diseases such as heart disease and stroke. It also increases the risk for various forms of cancer. Unfortunately, it also turns out to be one of the most difficult problems to prevent. “This is mainly because there are so many factors that influence why a person has obesity or overweight,” adds Lakerveld.

In order to investigate these multifactorial causes of obesity, Amsterdam UMC is launching the OBCT Project, with funding from the Horizon Europe Programme and partners from the UK, Poland, Ireland, Norway, Denmark, Finland and Spain. The breadth of this European alliance allows the study to analyse data from millions of individuals across Europe.

"We look at groups of people with different economic, social and cultural backgrounds, because what is important to one group might not necessarily be applicable to everyone," says Lakerveld. The results of this long-term study will support researchers, policymakers, but above all health professionals in achieving the goal of minimizing the burden of overweight and obesity across Europe.

Obesogenic environments

“We are going to tap into existing data in a different way, among other things. For example, there is a lot of data about the location and density of various food outlets, including (fast food) restaurants. This allows you to analyse whether certain neighbourhoods have a healthy or unhealthy food environment. We also look at the walkability of neighbourhoods, and other factors that support an active lifestyle,” says Lakerveld.

"While the environmental data we're going to use is abundant and often publicly available, it has not been effectively used in public health research. But it can lead to staggering insights. For example, we have previously shown that people who reside in more car-dependent neighbourhoods develop diabetes more often,” adds Lakerveld.

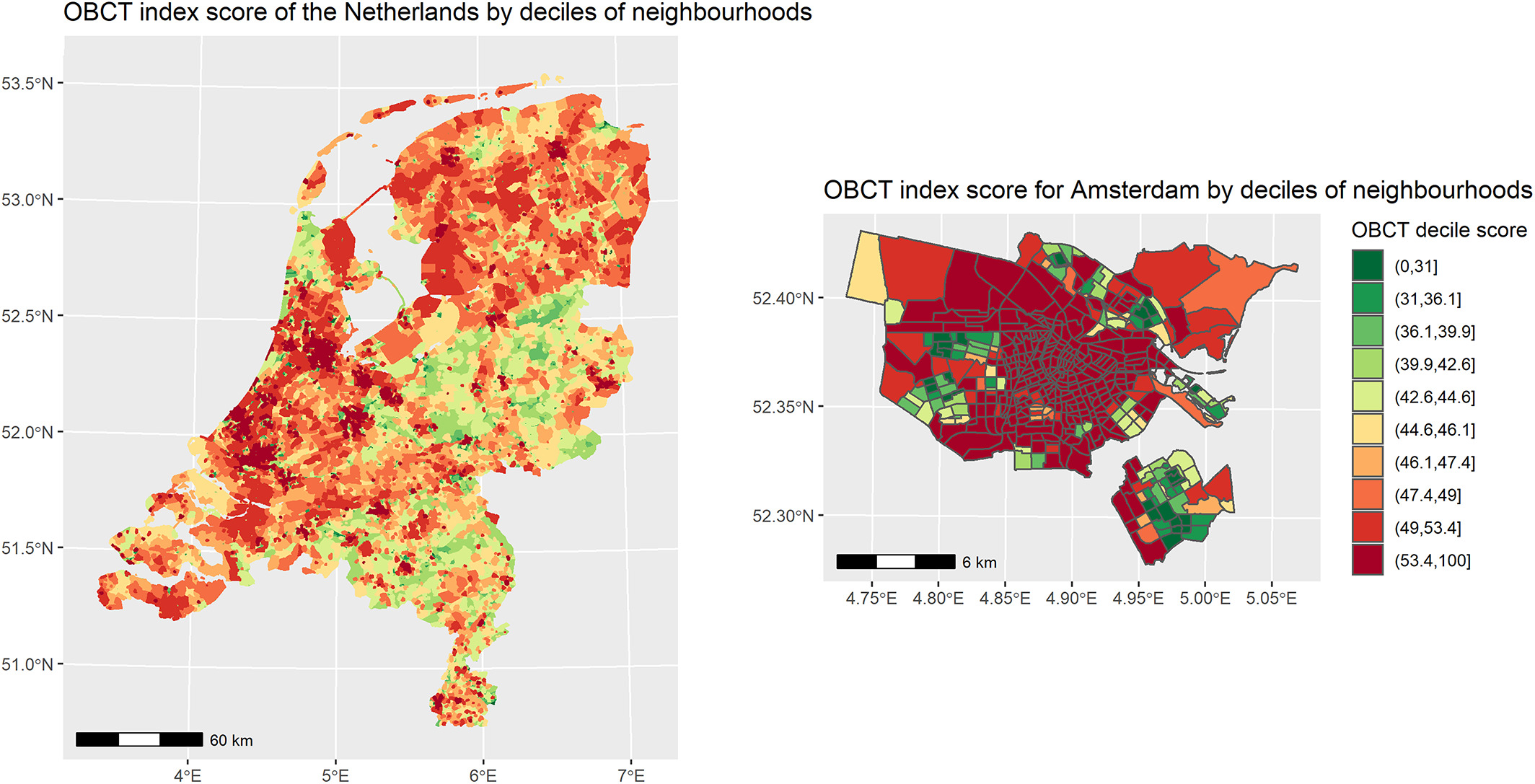

"With OBCT we want to map out what 'obesogenic' environments look like in different European countries. This heatmap enables us to identify where the problems are or will arise in the future.” The Amsterdam UMC team has already compiled an obesity risk map based on environmental characteristics of each neighbourhood in the Netherlands, and this will facilitate the project in, ultimately predicting an individual's risk of obesity.

OBCT index score for all neighborhoods in the Netherlands (left) and the municipality of Amsterdam (right) in 2016. Darker red indicated higher obesogenicity. The score is graphically presented in deciles. OBCT, Obesogenic Built Environment CharacterisTics

OBCT index score for all neighborhoods in the Netherlands (left) and the municipality of Amsterdam (right) in 2016. Darker red indicated higher obesogenicity. The score is graphically presented in deciles. OBCT, Obesogenic Built Environment CharacterisTics

Holistic approach

Obesity is not simply a result of poor diet and lack of exercise. “Rather, it involves a complex interplay of genetic, biological, socio-cultural and environmental factors. Whether you live in an obesogenic neighbourhood, whether you are rich or poor etc and so on, these factors are intricately linked to each other, and together they lead to an unhealthy lifestyle,” says Lakerveld.

“So, you have to be able to turn different dials to ensure optimal conditions for maintaining a healthy weight. It requires a holistic approach. And the perspectives of the persons concerned are very important in this. We want to be able to learn from each other. It is important to work with the target group and the 'people on the ground' to see what will really help in the fight against obesity,” concludes Lakerveld.