CAR-T cell therapy, an innovative form of immunotherapy, can be lifesaving for some people with a very aggressive form of lymphoma who are otherwise out of treatment options. Marie Jose Kersten, professor of hematology and head of the department of Hematology at Amsterdam UMC, was interviewed about this treatment method by het Eindhovens Dagblad. In the article below, the treatment is described by Prof. Kersten and illustrated with the story of Hans Hulsen who would not be alive today without this treatment.

'I love you guys.' Hans Hulsen must write down this sentence several times a day, If he can write that sentence, the side effects of his cancer treatment are not too bad. At least 29 times, it goes well. Then the sentence becomes illegible. But side effects or not, this treatment is Hans's last chance. A few months ago, he received CAR-T cell therapy at Maastricht UMC. CAR-T is an innovative form of immunotherapy that can be lifesaving for people with a very aggressive form of lymphoma who are otherwise out of treatment options.

As big as a tennis ball

Hans Hulsen from Sint-Oedenrode belongs to that group. It is March 2021 when he feels a lump in a place where it does not belong - on his chest on the right side, just below the shoulder."As big as a tennis ball," he says. It turns out to be non-Hodgkin's disease, an aggressive lymphoma.

Hans tells his story sitting on the sofa of his vacation home in Sint-Oedenrode. His wife Ria is at the table. She is the only one who is allowed to come close to her husband. The rest need to stay at least a few meters away. Hans has hardly any immune system left. The slightest infection can be fatal to him.

Within no time, the tumor started growing again

But Hans is still alive. For a while, it did not look good. At first, chemotherapy seemed to work and the tennis ball under his shoulder disappeared. Hans and Ria celebrated by going on vacation. "But in November, he felt something again," says Ria. "And he was right. Within no time, the tumor had started growing again." The tennis ball was back.

One last straw

A second round of chemotherapy did not help and the option of stem cell therapy was cancelled at the last minute. "My cancer was too bad, too aggressive," says Hans. Until a few years ago, this would have been the end of the line. Out of treatment options, it was time to think about the last wishes in the few months or weeks remaining. Now, however, there is one more chance, a new treatment that works for quite a few patients: CAR-T cell therapy. “Patients receiving this therapy are actually receiving a living drug," says Marie José Kersten, professor of hematology at the Amsterdam UMC.

A living drug

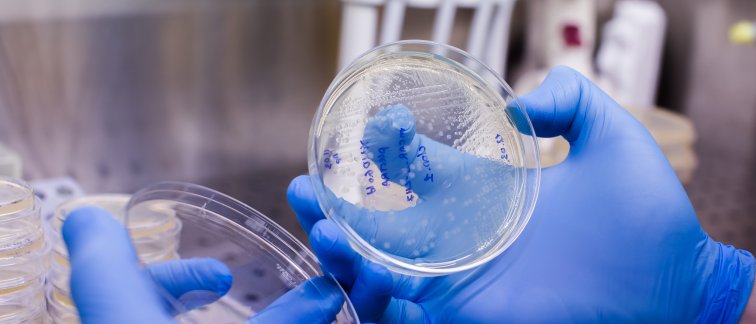

Prof. Kersten is an expert in CAR-T cell therapy and explains how the treatment works. "White blood cells, called T cells, are taken from patients via a kind of dialysis machine. These are then genetically altered outside of the body in a lab." T cells are part of our immune system and can fight cancer, but they do not always do so. Sometimes, they do not recognize a tumor as an invader. When that happens, tumors can continue to proliferate undisturbed.

In CAR-T cell therapy, the Tcells learn to recognize a proliferating tumor. Prof. Kersten: “In the lab, the T cells are infected with a harmless virus that carries a piece of DNA instructing the Tcell to produce a certain protein. This protein ends up on the outside of the Tcell, like a kind of grabber that recognizes the cancerous cell so it can bind to it and launch an attack.”

"You give a patient back millions of their own cells now with a specific 'antenna' for the cancer cells," Prof. Kersten says. "It's a living drug, once inside the patient, they start multiplying."

Not suitable for everyone and expensive

The therapy is relatively new and still under development. There can be serious side-effects and it is by no means suitable for everyone. Currently, only people with diffuse large-cell B lymphoma (a form of non-Hodgkin lymphoma) and acute lymphatic leukemia are eligible, only if previous treatments have failed.

"In lymphatic leukemia, the treatment has so far been approved only for children and young adults up to 25 years of age," Prof. Kersten says. Patients with other forms of lymphoma or multiple myeloma (bone marrow cancer) can now only be treated as part of a clinical study.

The treatment is currently very expensive. The modified T cells come from laboratories of corporate partners. "We get an invoice of 356,000 euros for a tube of cells," says Prof. Kersten."The total cost for a treatment runs to about 450,000 euros." New studies are therefore focusing on faster and cheaper production of CAR-T cells.

Every patient who may be eligible for this therapy is considered via consultation by Prof. Kersten and others. "We discuss the treatment option with about two hundred patients a year. Half of them actually receive the therapy."

Many dropouts

Of those who may be eligible for the therapy, there are many dropouts. Genetically changing the T cells takes four weeks and sometimes patients are too weak and cannot wait that long. Moreover, the side effects can be extreme and even life threatening.

“The cells you get back are supercharged. They go looking for tumor cells. Other immune cells are called in," Prof. Kersten says. "There's a chance of a cytokine storm, an overreaction of the immune system." Patients may develop high fevers and low blood pressure. "Sometimes they feel really miserable. They may have to go to intensive care for a few days. In very rare cases, this can be fatal."

The immune system also takes a hit because the T cells armed with their new protein (the grabber) also attack healthy B cells, which are also part of the immune system. Prof. Kersten: “B cells are switched off for a longer period of time after the treatment. This prevents the immune system from forming good antibodies against pathogens, such as the virus that causes COVID-19.”

The brain can also be affected by the treatment. Neurotoxicity, harmful side effects for the nervous system, usually occurs a few days after the cytokine storm. "A very strange phenomenon," Prof. Kersten muses. "It can happen suddenly. A patient can be lucid one moment and completely confused an hour later. We monitor that with memory tests and a writing test."

'I love you guys'

Hans Hulsen therefore writes 'I love you guys' several times a day at the hospital in Maastricht. Exactly 29 times, it went well. “The 30th time it went like this," says Ria, making big gestures with her right hand. "They were big scribbles. Unreadable. He was suddenly so confused."

Hans could not even manage to name the city he was in anymore. "I knew, but the word would not come out."That was three days after the treatment.

The tennis ball is gone

In the weeks that followed, Hans had a hard time. He was given a drug that makes him apathetic. He did not want to do anything anymore. “No watching television, no reading the newspaper, no eating," says Ria. "Just lie down, sleep. He did that for weeks." Hans lost 12 pounds.

But the tennis ball was gone. Hans: "That one was completely gone after about four days." A scan a month ago showed nothing. Hans was certainly not the only one for whom the treatment worked.

“The treatment initially has effect in 80 percent of patients,” Prof. Kersten says. “And in 50 percent we see a complete remission of the tumor. For about 40 percent, the benefit is permanent. Of those, we now dare to say that they are cured." She calls that last percentage extraordinary in light of the fact these patients had exhausted all other treatment options.

Time will tell if Hans stays free from cancer. If the tumor is still gone after a year, then chances are it will stay gone, according to Prof. Kersten. “Everything is gone. I'm happy with that," Hans says. "I hope they can still say that a year from now. And that it will continue like that." In any case, he feels a little better each day. Cautiously, Ria and Hans are planning their next vacation: "I really hope we can go out on the bike again, maybe in a few months."

Learn more about our innovative tumor research:

How do head and neck tumors create an immunosuppressive environment? (February 2022)

Tumors can hijack embryonic processes to escape immune surveillance (January 2022)

Source: read the original (Dutch) article by Merlijn van Dijk in het Eindhovens Dagblad here.