“The immune system is involved in all human diseases,” explains Yvette van Kooyk, Amsterdam UMC professor and head of its department of Molecular Cell Biology and Immunology. “It usually does great work, but it can also fail. In cancer, and in infectious diseases like HIV, the immune system is underactive and fails to remove tumor cells or pathogenic viruses. In auto-immune diseases like rheumatism and multiple sclerosis the immune system is overactive, and it attacks your own body.”

A key role for sugars

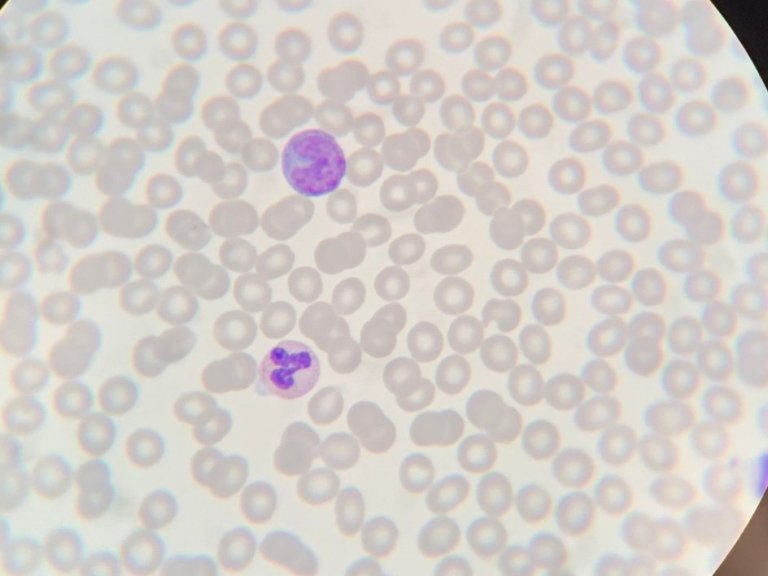

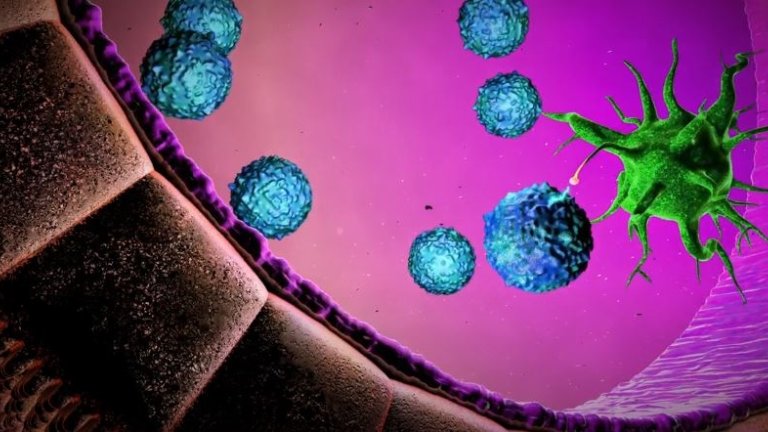

Van Kooyk can justly call herself the founder of a new field, glyco-immunology. Twenty years ago the prestigious journal Cell published her ground-breaking discovery: ‘glycans’, or sugars, play a key role in the communication between cells in the immune system in two articles. “We already knew that so-called ‘dendritic’ cells switched on the immune system in infectious diseases. They activated your T cells, and this started the build-up of immunity. But how did a dendritic cell make contact with a T cell? We discovered that it took place through a special receptor on the surface of the dendritic cell.” This receptor makes contact with sugar structures on the surface of the T cell. It also continuously samples its surroundings in order to detect any intruders that have specific sugars on their outer surface.

- Identification of DC-SIGN, a Novel Dendritic Cell–Specific ICAM-3 Receptor that Supports Primary Immune Responses.

- DC-SIGN, a Dendritic Cell–Specific HIV-1-Binding Protein that Enhances trans-Infection of T Cells.

Adverse outcome

With the help of these receptors the dendritic cells then absorb the pathogen in order to destroy it, while also activating T cells. But this beneficial process can also have an adverse outcome; for instance, HIV virus particles, just like other intruders, get attached to dendritic cells by their sugars – but the virus then exploits these cells, using them as an incubation site on which to multiply. “It’s a kind of Trojan Horse effect. The pathogens are not destroyed, but are spread through the body.”

Higher profile

In 2017 Van Kooyk commissioned a short film, Glycotreat, to explain this fascinating biological battleground in which friend and enemy can change places. The production promptly won Best Scientific Film at the Cannes Film Festival. Last year NWO awarded the researcher the Spinoza Prize of €2.5 million for outstanding and ground-breaking research.

How does she plan to spend the money? “I want to use some of it to give glyco-immunology a higher profile, and to make the complex research in this field more accessible to a wider audience,” she replies. “Pairs of researchers and artists will soon be working together to tell this story to a wider public.”

Improved cancer treatment

In recent years Van Kooyk has increasingly focused on research into cancer treatment, where there is still much room for improvement. The treatment of lung cancer and melanoma already makes frequent use of ‘immunotherapy’: drugs or vaccines that strengthen the immune system. However, many patients show a poor response to it, and better therapies are also needed in the treatment of pancreatic cancer and glioblastoma. “Immunovaccines will work better if the sugar coating around the tumor cell is breached at the same time,” she says. “Only then can the immune system destroy the tumor.”

The determination of a ‘glycosylation profile’ will often form part of the diagnostic process. This profile shows all the glycans present in the bloodstream or attached to a given protein. Comparing the profiles of healthy people with those of diseased individuals makes it possible to identify changes and relate them to the clinical picture. Big Data analysis and artificial intelligence are especially useful in this regard.

Analyzing the glycosylation profiles of large groups of patients is a pretty complicated business”

“Analyzing the glycosylation profiles of large groups of patients is a pretty complicated business,” says Van Kooyk. “But it’s allowing us to get better at distinguishing between different groups of cancer patients, and estimating their chances of survival. As a result, lung cancer patients, people with melanoma and with pancreatic cancer are being classified with ever greater precision, which means that clinics can offer them more individually-tailored treatment.”

Combination

Naturally, it is hoped that in the near future it will become possible to accurately predict how any given cancer patient will respond to a certain therapy. “It’s always discouraging if an invasive cancer treatment fails to yield any benefit,” explains Van Kooyk. “A more personalized treatment could help to prevent that disappointment.” There are also vaccines in the pipeline, dendritic cell vaccines and nanovaccines for instance, to give the immune system a boost. “In the long term we might be able to combine them with immunotherapy in order to counteract the suppression of immunity, making the body more susceptible to the treatment.”

This promising research, which often requires expensive new technology and large-scale experimentation, is only possible if forces are joined. Van Kooyk: “Amsterdam UMC is working to set up an ImmunoTherapyCenter where medics and research groups, each with their own research questions, can innovate together more quickly. The idea is to combine shared interests so as to enable the analysis of as much patient data as possible. The Spinoza Prize has definitely helped to advance these new developments, both as a source of funding and of recognition.”