"We hope to be able to develop a preventative vaccine by designing and testing immunogens that will induce neutralising antibodies. So far, no one has managed this,” says Sanders, Professor of Virology at Amsterdam UMC.

Developing a HIV vaccine has proven, so far, impossible but in Sanders' view there are reasons to be positive. “There’s quite a lot of optimism at the moment in the HIV vaccine field because of developments in early phase research. There are quite some positive results from several Phase I studies on trying to induce broadly neutralizing antibodies,” Sanders explains. “All the vaccines that failed so far have not been able to induce neutralising antibodies, let alone broadly neutralising antibodies. But there’s very nice progress compared to these earlier studies.”

Building on progress

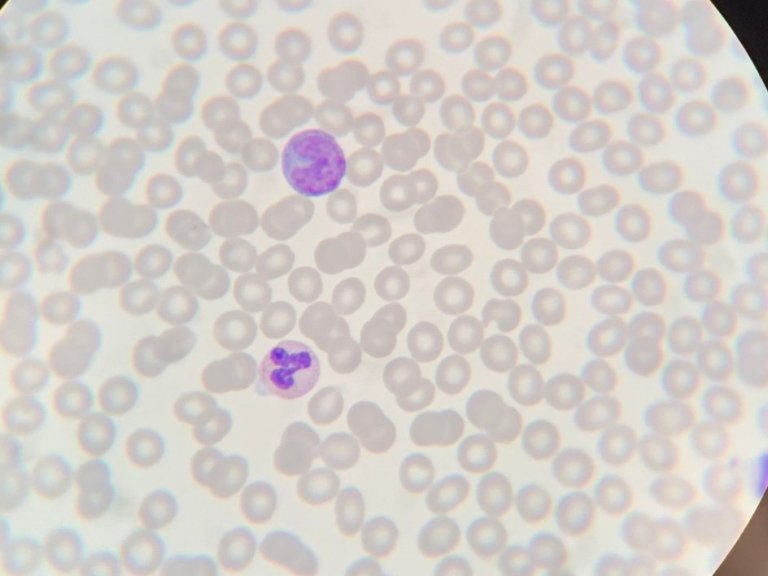

His team, consisting of researchers from Stanford University, Weill Cornell Medical College and the University of Louisiana, aim to build on this 'nice progress' by developing a vaccine that specifically targets rare immune cells that are capable of making antibodies that neutralize the virus. Known as 'Germline Targeting', this process guides the immune system by activating immune cells that have the potential to grow and produce antibodies that react against a HIV infection. This process has already been shown to work, in a study published but another research team in Science, earlier this year.

Sanders’ team are also currently busy with their own study in search of a vaccine that can stimulate immune cells into producing antibodies. The next step is to develop ways of boosting immune response, through a process known as 'priming, shaping and polishing,' where these cells are then guided through a development process so that they can ultimately produce stronger and broader antibodies.

"Think of the human immune cells in terms of a youth football team. First, the germline-targeting vaccine scouts and recruits the talents from this youth team, then once the right cells have been primed, through multiple phases of training, the shaping and polishing vaccines, the talented players are eventually shaped into world class football players,” says Sanders. This process may ultimately lead to immune response that is strong enough to repel a HIV infection and, thus, a fully functioning vaccine.

Unusual features

While this sounds simple, the hunt for an HIV vaccine has puzzled virologists. Since the 1980s, there has still not been a successful phase III study among a large group of subjects. This is mainly due to the unusual properties of HIV. "There are so many things to consider," Sanders explains. "There are a number of reasons why it is so difficult to make a vaccine and one of them is the diversity of the virus. A second difficulty lies in the structural or chemical properties of the protein that surrounds the virus, which is crucial for vaccines."

Sanders' team recently took an important step forward with a 'priming' vaccine that was tested in a phase I study in test subjects in New York, Washington and Amsterdam (at Amsterdam UMC). "We are hopeful that we will eventually succeed in developing an effective vaccine against the many variants of HIV. Hopefully, that will put an end to the ongoing misery that the virus brings," Sanders says.