Stomach ache, fatigue and worrying about where the closest bathroom is located. For many Crohn’s disease patients, this is an everyday reality. “We would like to identify patients earlier, so we can start treatment early and prevent severe symptoms, and maybe one day prevent Crohn’s disease from happening”, Geert D’Haens, gastroenterologist at Amsterdam UMC, says.

Current treatment is based on a trial-and-error approach, resulting in patients having to try out different treatments before they can find the “ideal” one, sometimes, without any success at all. On top of that, Crohn’s disease is often diagnosed far beyond the start of the disease, even after initial symptoms begin, which means that permanent damage has already occurred.

Crohn's disease needs to be detected earlier

As has already been shown for Diabetes Type 1 - a disease where the immune system does not function properly leading to chronic inflammation and tissue damage - finding out early on if someone could develop the disease could make a big difference for future patients. In other diseases in which the immune system does not function properly, like Crohn’s disease, but also rheumatoid arthritis, such early detection could also make a big difference.

Large studies in the United States and Canada have already shown that people who later developed Crohn’s disease had biological changes in their blood - so‑called biomarkers - before diagnosis suggesting that Crohn’s shows signs long before symptoms appear. These biomarkers included shifts in immune system signals (antibodies against proteins - the building blocks of our cells - and against microbiomes) and increased permeability of the intestine (how easily things move inside and outside your intestine).

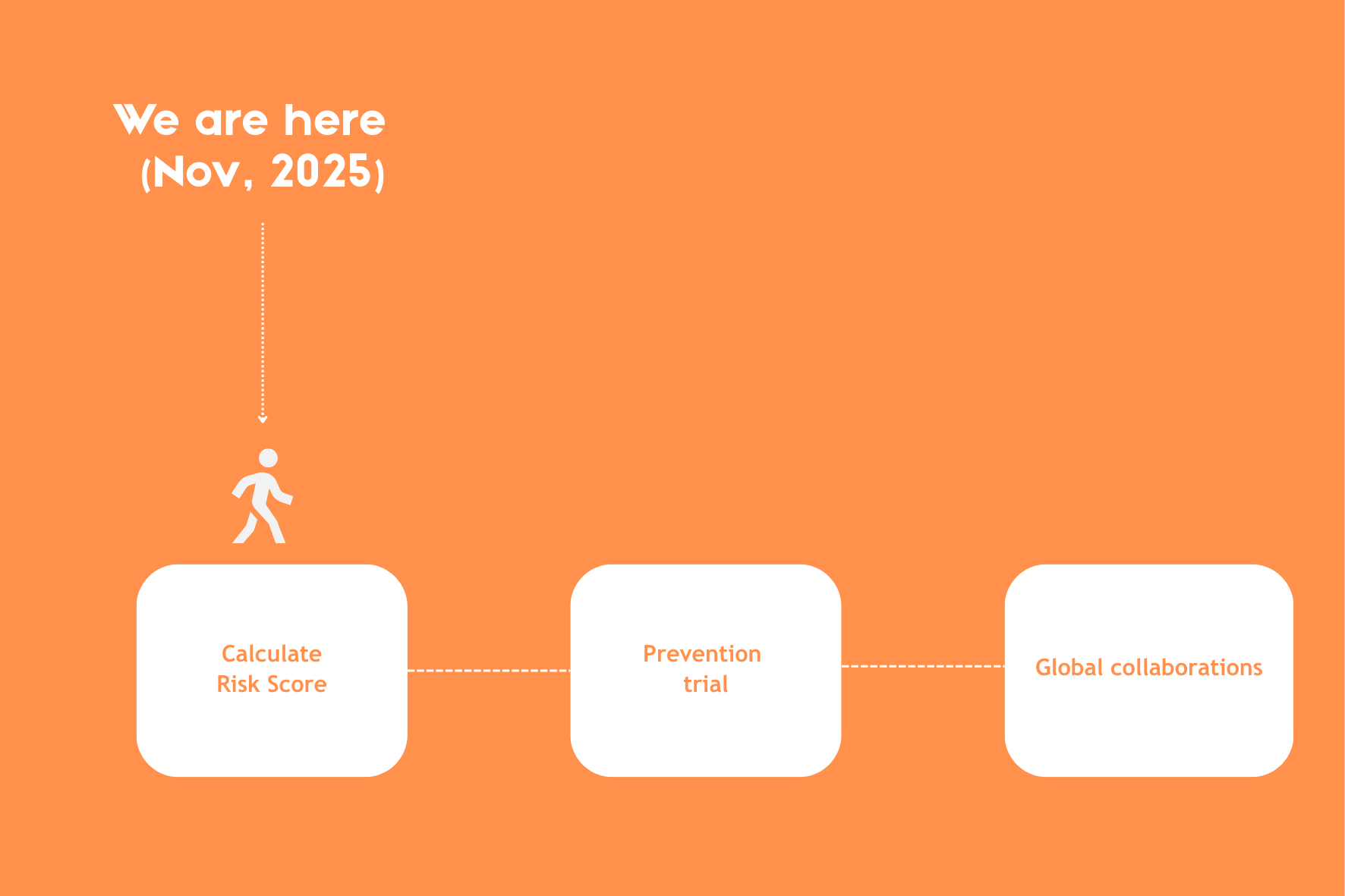

Building on this biomarker knowledge, INTERCEPT, an enormous scientific collaboration across multiple countries, was set up. Project coordinator Geert D’Haens and gastroenterologist Rogier Goetgebuer explain that INTERCEPT hopes to identify who is most likely to develop the disease and which treatments work best. They aim to do so by developing a tool to determine the risk of developing Crohn’s disease, and then treating a group of high-risk patients preventatively before they develop severe symptoms.

Developing the risk score and intercepting the disease

To create these risk scores, 10,000 first-degree relatives of Crohn’s disease patients across Europe will be recruited. That is because first-degree relatives have roughly an 8-fold increased risk of developing the disease when looking at genetic and environmental factors. Blood and stool samples from these participants will then be analyzed to calculate their risk scores.

Once these risk scores have been calculated, the second part of INTERCEPT will invite 80 participants with a high‑risk score to take part in an innovative prevention trial. In this trial, proven medical treatments will be used to intercept disease progression before severe symptoms even appear.

The third stage will focus on partnering up with other parties to build on the science uncovered in this study. While improving the detection and treatment of Crohn’s disease is the main driver of INTERCEPT, extending this biomarker research to help intercept other diseases also aligns strongly with the goals of stage 3.

PhD candidate Inge Boukema also tells us, “The plan is to integrate the risk score into a digital health app and share it with healthcare providers.” Additionally, INTERCEPT envisions high‑risk clinics where people with an at‑risk profile could receive testing and care. From a societal and ethical perspective, this could reduce the overall costs of Crohn’s disease, since fewer people would become severely ill and fewer would drop out of work.

Still, population screening programs such as the Dutch national Colorectal Cancer screening program show that such efforts can bring psychological stress and other burdens. As independent ethicist Steven Kraaijeveld of VU Amsterdam notes, “Everyone has a right not to know, and that’s something the study must handle with care.”

Ethics and early detection

Clearly, ethical considerations in such big early detection studies are important. Beyond the need to safeguard the privacy of biological data collected from 10,000 people, deeper questions arise: is it ethical to screen thousands and provide risk scores, knowing that most will never develop the disease? And could the benefits of prevention outweigh the risks of over‑treatment or the psychological burden of living with a “high‑risk” label?

Inge Boukema is part of the INTERCEPT ethics board and described the participants’ perspectives from the initial focus group interviews. The general consensus was that family members were eager to join the study and receive a risk score.

"It's better to know than not to know"

At the same time, family members expressed apprehension about undergoing the steps required to calculate a risk score if they would not ultimately receive that score. These focus group interviews highlighted perspectives that INTERCEPT can use to shape the study. For instance, participants will be given the choice of whether they wish to know their risk score.

A similar hesitation applied to preventative medical treatments in stage two, with participants anticipating being less willing to proceed as the invasiveness of procedures increases, though those participants have not yet been selected.

Even before conducting the focus groups, the INTERCEPT project carried out a large survey among people at higher risk of developing Crohn’s disease to ensure ethical considerations were addressed. The survey revealed a clear trend: the more invasive the methods used to determine risk scores, the less willing people were to undergo them. Because this concern repeatedly surfaced in communications with the target group, INTERCEPT is working to replace traditional colonoscopies with video capsules in their study, a less invasive way to observe the intestines.

The European Federation of Crohn’s & Ulcerative Colitis Associations was closely involved in designing and implementing the study. Taken together, these steps reflect INTERCEPT’s commitment to upholding the highest ethical standards.

Lab logistics of a study of this magnitude

One of the main challenges in carrying out such a large study is managing the thousands of samples collected, especially since they must all be shipped from different countries and stored together in Amsterdam. This requires the expertise of lab specialists, biobanks, and project managers, as well as a dedicated sample‑tracking website and even legal support to navigate country‑specific shipping laws.

To make sure samples are collected in the same way everywhere, special kits were designed and sent to all the countries taking part, with instructions translated into several languages. Using these kits, researchers gather serum (the clear part of blood), stool, and whole blood, all of which eventually make their way to Amsterdam. To be safe, four serum samples are taken from each participant: one for immediate use, two for long‑term storage in biobanks, and one that stays at the local institute where it was collected.

Illustration by: Valentina Bravo

Illustration by: Valentina Bravo

That adds up quickly, around 40,000 serum samples in total, so special tubes that are about ten times smaller than standard ones had to be ordered. This saves a huge amount of space. Each tube and storage box also carries a barcode, making it much faster to keep track of everything. In the end, all those samples fit into just 110 boxes in a freezer kept at –70°C.

Wouter de Jonge, Professor of Experimental Gastroenterology, explains that ultimately, what can really make such an intricate research plan work is passion, a strong network, and good communication with the whole team involved. Postdoctoral researcher Isabelle van Thiel adds a crucial tip: “While setting up the infrastructure for a big study, always include the lab staff who will collect, store, and process the thousands of samples. This will ensure the most uniform samples, and in turn, the cleanest data.”

How to build a study this big

INTERCEPT’s success has been built on collaboration and trust across a diverse network of hospitals, research teams, and industry partners. From the start, professional grant writers helped shape the proposal, allowing the consortium to prepare rapid, well‑structured applications, including the successful submission to the Innovative Health Initiative. The study also benefited from support by industry partners such as Takeda, and from specialized laboratories spread across Europe and beyond.

Together, these elements created an efficient, multidisciplinary research infrastructure that now drives INTERCEPT’s progress. Close coordination, clearly defined roles, access to biobanks, and expertise in bioinformatics and laboratory testing proved crucial. This combination of trust, technical capacity, and shared ambition shows how an integrated network can accelerate the development of preventive strategies for Crohn’s disease.

Authors

Femke Mol

Marte Molenaars

Valentina Bravo